Assessment of stridor in children

INTRODUCTION — Stridor describes a high-pitched, monophonic sound.

These characteristics distinguish stridor from typical wheezing due to diffuse airflow limitation (asthma or bronchiolitis), which tends to consist of multiple sounds that start and stop at different times.

Stridor is caused by the oscillation of a narrowed airway, and its presence suggests significant obstruction of the large airways.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

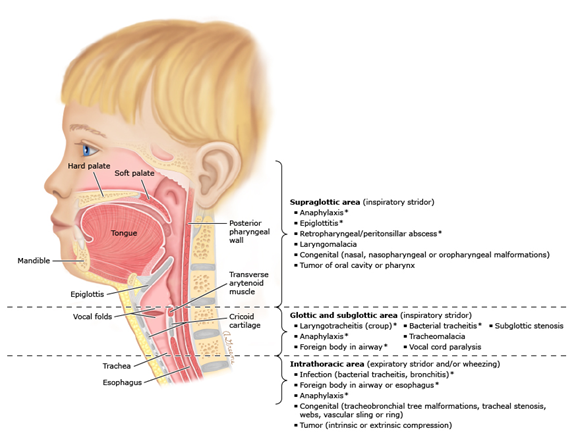

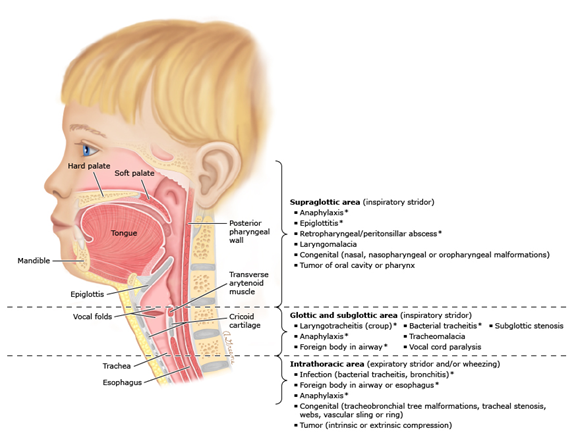

Anatomy — Anatomically, the large airways can be divided into the extrathoracic and intrathoracic regions:

Extrathoracic — The extrathoracic region includes airways above the thoracic inlet, which, in turn, can be subdivided into two anatomic areas:

- Supraglottic area– This area includes the nasopharynx, epiglottis, larynx, aryepiglottic folds, and false vocal cords. The walls supporting this region are made of soft tissue and muscles, and lack cartilaginous support. Therefore, airway collapse and obstruction can occur easily and progress rapidly in this area.

- Glottic and subglottic area– This portion of the airway extends from the vocal cords to the extrathoracic segment of the trachea, just before it enters the thoracic cavity. The glottic area has some cartilaginous support (ie, cricoid cartilage and incomplete tracheal rings), which makes it less vulnerable to collapse than the supraglottic area. The subglottis, surrounded by the cricoid cartilage, is the narrowest part of the trachea. The diameter of the subglottis is 5 to 7 mm at birth and steadily increases to an average diameter on 20 mm in adults. In the narrow airway of an infant, a small decrease in diameter dramatically increases the airway resistance (because resistance is inversely proportional to the radius to the fourth power [r4]). As an example, a narrowing by 1 mm in the subglottic area in an infant will decrease the cross-sectional area by approximately 50 percent and increase airway resistance 16-fold.

Intrathoracic — The intrathoracic region includes the portion of the trachea that lies within the thoracic cavity, as well as the main stem bronchi. Compression of the proximal trachea can result in expiratory stridor, whereas compression of the more distal intrathoracic airways tends to cause typical polyphonic wheezing rather than stridor. Congenital disorders are a prominent cause of obstruction at this level (eg, vascular rings and webs). Foreign bodies and compression by enlarged lymph nodes or tumors can also occur at this level

- Inspiratory stridor– In general, stridor originating from obstruction in the extrathoracicregion is more pronounced during inspiration, when the pressure inside the airway falls below atmospheric pressure, causing airway collapse

- Expiratory stridor– In contrast, stridor originating from obstruction in the intrathoracicregion is more pronounced on exhalation, since intrathoracic pressure rises on expiration and causes airway collapse

- Biphasic(inspiratory and expiratory) stridor– A fixed central airway obstruction usually produces noise on both inspiration and expiration. Conditions causing fixed airway obstruction include external compression, intraluminal airway masses (eg, hemangioma or foreign body), and subglottic stenosis.

- Stertor or snoring– If airway narrowing originates from the nasal, nasopharyngeal, or oropharyngeal areas (ie, adenoid hypertrophy, micrognathia, macroglossia, and tonsil hypertrophy), the noise generated is typically low pitched. It may be referred to as snoring if it occurs when the patient is sleeping, and stertor if it is present when the patient is awake.

CAUSES OF STRIDOR — Stridor may result from a variety of conditions that can be either congenital or acquired. The age of the patient and acuity of onset helps to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Acute onset — A variety of causes of acute upper respiratory obstruction can manifest as stridor. Symptoms develop within minutes or a few hours, and may progress rapidly.

- Foreign body aspiration– Foreign body aspiration should always be suspected in an infant or toddler who presents with sudden or intermittent onset of stridor, with or without respiratory distress, and without other physical findings. Its incidence peaks around two to three years of age. If an infant is in an environment with older children, foreign body aspiration can occur at an earlier age. A history of a witnessed choking episode is common, but may not be recalled by the caregiver because it appeared to resolve.

- Anaphylaxis– Anaphylaxis (most commonly caused by food or medications) is a common cause of acute-onset stridor, and may be severe and life-threatening, particularly when edema involves the retropharynx and/or larynx. Common manifestations include respiratory symptoms (change in voice quality, choking, stridor, wheezing, drooling, or cough), skin symptoms (hives, itching, and mouth swelling), and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain). Presenting symptoms in infants are similar but can be more difficult to recognize.

- Infectious causes

- Bacterial tracheitis– Bacterial tracheitis (or acute bacterial laryngotracheobronchitis) generally occurs during the first six years of life but may occur at any age. Most patients have prodromal symptoms and signs suggestive of viral respiratory tract infection for one to three days before more severe signs of illness develop, including stridor and respiratory distress, often with cough and a preference to lie flat. Although uncommon, it is among the most frequent pediatric airway emergencies requiring admission to an intensive care unit (ICU)

- Epiglottitis– Epiglottitis is inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent supraglottic structures. Without treatment, it can progress rapidly to life-threatening airway obstruction. Young children classically present with respiratory distress, anxiety, and fever, often with dysphagia, drooling, and muffled speech, and reluctance to lie flat. In the past, epiglottitis commonly occurred between two and seven years of age. Since the introduction of the H. influenzae type B (HIB) vaccine, the incidence of epiglottitis has dropped dramatically; however, there are still case reports of HIB epiglottitis occurring despite immunization. The peak age of epiglottitis is now greater than seven years, but epiglottitis can occur at any age

- Airway burns

- Thermal epiglottitis and upper airways burns– Microwave-heated liquids are the most common cause of thermal epiglottitis and edematous arytenoidal tissue in infants and young children. The clinical presentation of thermal epiglottitis injuries in children may be similar to that of acute infectious epiglottitis, and should be managed as an emergency airway obstruction. Airway burns also should always be considered in any child with body scald burns who presents with stridor or respiratory distress. Smoke or steam inhalation can cause direct thermal injury to the upper respiratory tract.

- Caustic burns– Ingestion or inhalation of caustic materials (such as powdered detergents) can injure the upper airway and epiglottis, causing stridor. Accompanying symptoms of vomiting, difficulty swallowing, and oropharyngeal swelling may resemble anaphylaxis.

Subacute onset — The following disorders typically present with respiratory symptoms that progress gradually to stridor (eg, over the course of a few days):

- Laryngotracheitis (croup)– Croup accounts for more than 90 percent of all cases of stridor in children. It most commonly occurs in children 6 to 36 months of age. It is also seen in younger infants (as young as three months) and in preschool children, but is rare beyond age six years. The onset of symptoms is usually gradual, beginning with nasal irritation, congestion, and coryza, and progressing to inspiratory and sometimes expiratory stridor. Symptoms generally progress over 12 to 48 hours to include fever, hoarseness, barking cough, and stridor. Croup is usually a mild and self-limited disease, but occasionally causes significant respiratory distress and can be life-threatening. A spasmodic form of croup is characterized by brief recurrent episodes of stridor, occurring at night. For children with a typical presentation of croup, confirmation of a viral cause is not necessary, since croup is a self-limited illness that usually requires only symptomatic therapy.

- Retropharyngeal abscess– Most retropharyngeal abscesses occur in children between two and four years of age. Early in the disease process, the findings may be indistinguishable from those of uncomplicated pharyngitis. As the disease progresses, symptoms include fever, dysphagia and drooling, unwillingness to move neck, muffled or “hot potato” voice, and inspiratory stridor.

- Peritonsillar abscess– Peritonsillar abscess generally arises as a complication of tonsillitis or pharyngitis. Its incidence peaks in children older than 10 years of age, when streptococcal pharyngitis becomes more common. The typical clinical presentation is a severe sore throat (usually unilateral), fever, muffled or “hot potato” voice, sometimes with inspiratory stridor, drooling, trismus, or neck swelling.

Chronic/recurrent — Chronic stridor is typically caused by a structural abnormality that may be congenital or acquired, static, or slowly progressive, leading to intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction of the upper airway.

Congenital — Most of the congenital lesions present during the first few weeks of life, but symptoms may be intermittent, and some anomalies such as bronchogenic cysts and laryngeal clefts may present later in infancy or childhood

Congenital anomalies associated with stridor

| Malformation | Characteristics |

Nose* | Nasal deformities | Choanal atresia or agenesis, septum deformities, turbinate hypertrophy, vestibular atresia, or stenosis. |

Pharynx* | Craniofacial anomalies | Anomalies causing facial retrusion are associated with upper airway obstruction, including Crouzon, Pierre Robin, and Apert syndromes. |

Tongue | Macroglossia and glossoptosis. |

Larynx | Laryngomalacia | Most common cause of chronic stridor in infants. Almost all patients present by six weeks of age. Symptoms are more pronounced after upper respiratory infections. |

Laryngeal webs | 75 percent located in the glottic area. Complete webs cause respiratory distress at birth, partial webs produce stridor, weak cry, and different degrees of respiratory distress. Associated anomalies are common. |

Laryngeal cysts | Located in supraglottic area may cause respiratory distress and stridor. |

Laryngeal clefts | Characterized by abnormal communication between the larynx and pharynx, sometimes extending downward between the trachea and esophagus. Patients may present with aspiration, cough, swallowing difficulties, respiratory distress, hoarse cry, or occasionally with stridor; often associated with other congenital anomalies. |

Subglottic hemangioma | Presents as with stridor and respiratory distress, usually worsening during the first few months of life. Often associated with cutaneous hemangiomas. |

Subglottic stenosis | May be congenital but more often acquired secondary to intubation. Usually located 2 to 3 mm below the glottis. |

Vocal cord paralysis | Idiopathic, or secondary to a neurologic disorder (including Chiari II malformation, hydrocephalus, meningomyelocele, hypoxic cerebral palsy, and cerebral hemorrhage).[1,2] |

Trachea¶ | Tracheal stenosis | Usually presents with stridor or both stridor and wheezing. If stenosis is significant, respiratory distress occurs. |

Vascular rings or slings | 74 percent of vascular rings are symptomatic. The airway compression usually is intrathoracic, causing expiratory stridor. Associated anomalies are common. |

Tracheomalacia | Often associated with other congenital anomalies. May be secondary to a vascular ring or cysts. Worsens with upper respiratory infections, crying, coughing, or feeding. May cause severe spells with cyanosis. |

Bronchi and distal airways¶ | Bronchogenic cyst | May occur at any point throughout the tracheobronchial tree. Typically present during childhood with recurrent coughing, wheezing, or pneumonia, but may become symptomatic during infancy or adulthood, or present as an incidental finding on chest radiographs. |

* Noise generated from the nose or pharynx is typically low in pitch and is referred to as snoring or stertor.

¶ Noise generated from the trachea, bronchi or distal airways is mostly wheezing.

- Laryngomalacia– Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of chronic extrathoracic airway obstruction in infants. It typically presents during the neonatal period and progresses during infancy, but resolves by 12 to 18 months. The stridor is inspiratory and tends to be worse in the supine position and during feeding and sleeping.

- Tracheomalacia– Tracheomalacia usually is caused by an intrinsic defect in the cartilaginous portion of the trachea leading to an increased proportion of membranous trachea (type 1). Most lesions are intrathoracic, causing airway collapse and stridor during expiration, often with a croup-like cough. Most affected infants improve spontaneously by 6 to 12 months of age as airway caliber increases and cartilage develops.

- Vocal cord paralysis– Vocal cord paralysis may be associated with neurologic or cardiac malformations, due to trauma at delivery, or idiopathic. Infants with bilateral paralysis typically present with stridor and respiratory insufficiency, and may have normal cry. Those with unilateral paralysis tend to present with hoarseness and are at risk for aspiration.

- Vascular ring– Vascular rings (including a pulmonary artery “sling”) cause stridor due to external compression of the trachea. The presentation varies from marked respiratory distress in neonates to intermittent stridor in infants and young children. Because the compression is intrathoracic, the stridor usually is loudest in the expiratory phase. In some cases, the esophagus is also compressed, leading to dysphagia, hyperextension of the head during feeding, or other feeding difficulties. Associated anomalies are common, especially cardiac defects.

- Laryngeal malformations– Congenital malformations of the larynx include cysts, stenosis, clefts, and webs. They may present in infancy or early childhood with feeding difficulty, failure to thrive, wheezing, stridor, noisy breathing, aspiration, respiratory distress, recurrent pulmonary infections, and/or hoarseness. Clefts and webs are often associated with other congenital anomalies.

- Infantile hemangiomas– Infantile hemangiomas occasionally affect the larynx or trachea and cause intermittent stridor or respiratory distress, usually increasing during the first few months of life. Hemangiomas of the skin are present in approximately one-half of patients with subglottic hemangiomas. The risk of airway hemangioma is higher with segmental hemangiomas located in a cervicofacial, mandibular, or “beard” distribution.

- Subglottic stenosis– Subglottic stenosis can be either a congenital anomaly, or acquired.

Acquired

- Vocal cord dysfunction or paradoxical vocal fold motion – Vocal cord dysfunction typically presents with recurrent acute episodes of dyspnea and stridor; it may be misdiagnosed as asthma or occur concurrently with asthma.The stridor is more pronounced with exercise and resolves during sleep. Patients may complain often with throat tightness, a choking sensation, dysphonia, and cough. The disorder may begin at any age, but most commonly presents during adolescence and is sometimes but not always associated with psychosocial disorders and stress

- Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP)– RRP may be caused by human papilloma virus (HPV) type 6 or type 11. It is characterized by papillomatous growth of the epithelium of the airways (larynx and trachea). RRP has a bimodal age distribution and manifests most commonly in children younger than five years (juvenile-onset) or in persons in the fourth decade of life (adult-onset). The larynx is frequently affected. Patients can present with chronic or progressive stridor, hoarseness of voice or weak cry, choking episodes, cough, and wheezing if trachea is also involved. In some cases, upper airway obstruction may be life-threatening and may be the presenting symptom.

- Vocal cord paralysis– Acquired vocal cord paralysis may be idiopathic, iatrogenic (eg, after cardiothoracic or thyroid surgery or endotracheal intubation), or caused by neurologic abnormalities or injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The pattern of onset may be acute, subacute, or intermittent, depending on the cause. Children with bilateral paralysis typically present with stridor and respiratory insufficiency, and may have normal voice/cry. Those with unilateral paralysis tend to present with hoarseness and are at risk for aspiration.

- Subglottic stenosis– Subglottic stenosis can be either acquired due to injury to the glottis after traumatic or prolonged endotracheal intubation in infants, or a congenital anomaly.

- Hypocalcemic laryngeal spasm– Laryngeal spasm due to hypocalcemia has been reported as a cause of stridor in pediatric populations. Most reports are in infants with vitamin D deficiency and rickets secondary to dietary insufficiency, but some cases have occurred in the setting of other metabolic and endocrine disorders that lead to severe hypocalcemia, such as renal failure and hypoparathyroidism. The associated stridor can be chronic or intermittent but also may present with acute severe onset.

- Tumor– Any tumor that compresses the airway may present with stridor. Most are intrathoracic (eg, mediastinal) and extrinsic to the airway; this typically results in expiratory stridor.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Initial rapid assessment — The initial evaluation of children with stridor must begin with a rapid assessment to identify patients who need immediate intervention. Key steps are to evaluate upper airway patency, the degree of respiratory effort, evidence of hypoxemia and fatigue, and to monitor closely for the possibility of rapid deterioration. Diagnostic testing may need to be delayed to provide appropriate supportive care. In an acutely ill patient, diagnostic testing should only be performed in a controlled setting and with close supervision by a clinician who can intervene if the patient’s respiratory function deteriorates.

For children with stable respiratory status, the next step is a detailed history and physical examination to identify the cause of the stridor. In some cases, additional diagnostic testing, including radiography, pulmonary function testing, or airway visualization, may be required.

History — Key elements of the history serve to focus the likely causes of stridor

Age — Age of onset is an important determinant that can help identify the cause of stridor.

- Neonates and infants – Congenital disorders generally present in the first few weeks of life.

- Infants and toddlers – Croup is the most common cause of stridor in this age group. Foreign body aspiration is also an important consideration. Epiglottitis is uncommon but potentially life-threatening, and also occurs in older children.

- School-aged children and adolescents – Children in this age group are prone to peritonsillar abscess, as well as vocal cord dysfunction, which typically presents with recurrent episodes of stridor and dyspnea.

- All ages – Anaphylaxis and bacterial tracheitis are important considerations in any age group.

Acuity of onset — The acuity of onset and the severity of the symptom further narrows the cause of stridor.

- Acute onset

- Rapidly progressive symptoms with fever suggest epiglottitis or bacterial tracheitis. These serious bacterial infections typically present with respiratory distress, drooling, and gasping for air. These findings, which suggest a critically narrowed airway, signify an emergency requiring prompt medical attention

- Acute onset of symptoms without fever suggests foreign body aspiration or anaphylaxis.

- Subacute onset – Laryngotracheitis (croup) is the most common cause of stridor in children and tends to have a subacute or intermittent pattern. Peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscesses generally develop after symptoms of pharyngitis or tonsillitis.

- Chronic or recurrent – Chronic or recurrent episodes of stridor may suggest a subglottic stenosis or exogenous compression of the airway caused by a vascular ring or a tumor.

Associated symptoms — Additional symptoms that provide important clues are:

- Fever – Fever with toxic appearance suggests a serious bacterial infection (eg, epiglottitis, peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscesses or bacterial tracheitis). However, patients with a serious bacterial infection occasionally are afebrile on presentation to the physician. Fever is also common among children with laryngotracheitis (croup) but tends to be lower than in bacterial infections

- Mental status – Alteration in mental status (lethargy, anxiety) with increased work of breathing can point to an impending airway obstruction.

- Drooling – Drooling and a muffled voice usually suggest that the obstruction is supraglottic, including retropharyngeal abscess and epiglottitis. Drooling and dysphagia can occur with epiglottitis, a foreign body in the trachea, or a mass compressing the anterior esophageal wall.

- Cough – A barking cough is almost always present in laryngotracheitis (croup), and typically absent in children with acute epiglottitis, foreign body aspiration, and anaphylaxis.

- Voice tone – A change in the voice tone (hoarseness or pitch) suggests a laryngeal lesion such as vocal cord injury due to inflammation (eg, croup) or paralysis. A muffled voice suggests supraglottic obstruction, such as in retropharyngeal or peritonsillar abscess or epiglottitis.

- Stridor during feeding – Respiratory distress and stridor related to feeding can be caused by aspiration either secondary to swallowing dysfunction, certain types of tracheoesophageal fistula, or gastroesophageal reflux.

- Hives – Presence of rash, hypotension, and wheezing with acute onset of stridor indicates an allergic reaction with angioedema.

- Onset during sleep – If a patient develops airway obstructive episodes during sleep, it is most likely that the origin of the stridor arises from the pharynx, in which case, the tonsils and adenoids should be evaluated. Spasmodic croup also tends to present episodically during sleep.

- Onset during activity – If stridor is more significant while the patient is awake, and even more pronounced during exercise or agitation, then the possibility of vocal cord dysfunction or other laryngeal, tracheal, or bronchial obstruction should be suspected.

Past medical history — A thorough past medical history should be elicited, and should include the prenatal and perinatal period, including infections, prematurity, complicated delivery, necessity of intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Any significant surgical history (patent ductus arteriosus ligation, cardiac, or neck surgery) should be reviewed. It is important to learn whether there have been previous admissions secondary to respiratory diseases, and whether the patient ever required prolonged intubation. A history of food allergy or potential exposure to food or environmental allergens should be explored, especially in infants or children with symptoms suggestive of anaphylaxis.

Physical examination — If the initial rapid assessment determines that the patient is stable and immediate therapy is not required, then a detailed physical examination and diagnostic testing can be conducted.

- Skin and extremities – The skin should be inspected for hemangiomas, which, if present, suggest the possibility of a hemangioma in the airway. Café au lait spots are associated with head and neck neurofibromas, which can involve the airway. Lymphadenopathy suggests an intrathoracic process, such as infection or tumor compressing the airway. Clubbing may suggest an underlying congenital heart disease or bronchiectasis.

- Head, eyes, ears, nose and throat (HEENT) – Special notice should be given to the size of the tongue and mandible, and the presence of any craniofacial malformation. Surgical scars around the upper chest or neck are clues to a past procedure that might have contributed to vocal cord paralysis, or tracheal or subglottic stenosis. Neck edema accompanied by fever suggests a retropharyngeal or peritonsillar abscess.

- Respiratory – Breathing should be observed both during rest and after activity. The patient’s work of breathing should be assessed, including the presence of cyanosis, nasal flaring, and retractions. Children with epiglottis prefer to sit up in a “tripod” or “sniffing” position; this posture can also be seen in severe asthma or any cause of airway obstruction. Infants may instead extend their neck backwards in an effort to maximize upper airway patency.

This child’s “tripod” positioning (trunk leaning forward, neck hyperextended, chin thrust forward) is caused by epiglottitis and represents the patient’s attempt to maximize the patency of a significantly obstructed upper airway. Also, note the child’s toxic appearance.

Tripod positioning may also be seen in other causes of respiratory distress, such as severe asthma.

For auscultation, the stethoscope bell should be placed over the child’s mouth and neck to determine the origin of the stridor. Stridor is a high-pitched monophonic sound made during breathing, which is usually inspiratory and is heard best over the anterior neck. The character and timing of the stridor with the respiratory cycle provides a clue to its origin (see before)

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Laboratory — complete blood count (CBC) with white blood cell (WBC) count and differential. For children with a typical presentation of croup, confirmation of a viral cause is not necessary.

Radiography — Radiography is not necessary for a child with a typical presentation of croup. However, it can be a useful tool in evaluating a child with severe or atypical features, or other suspected causes of stridor, including foreign body aspiration. Prior to obtaining any radiographs, the clinician should evaluate the child and assess the risk of developing complete airway obstruction during the procedure. If any life-threatening situation is suspected, the patient must be accompanied to the radiology suite by appropriate medical personnel with the equipment necessary for airway management, including emergency tracheotomy or cricothyroidotomy. For children with suspected epiglottitis and stable respiratory status, radiography usually can be performed safely with close supervision. If the patient is unstable, an emergency evaluation of the airway in a controlled setting such as the operating room or the intensive care unit (ICU) is indicated.

Neck radiographs — Plain neck films are usually non-specific, but may reveal changes associated with retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, croup, or a radiopaque foreign body.

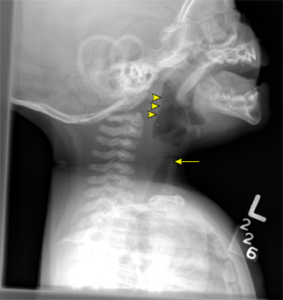

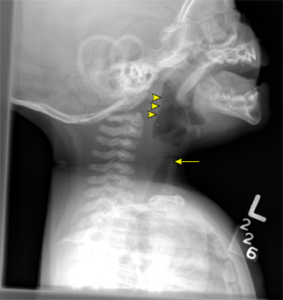

- Retropharyngeal abscess – Radiographic findings include a retropharyngeal space greater than 7 mm anterior to the inferior border of the second cervical vertebral body, or a retrotracheal space greater than 14 mm in children anterior to the inferior border of the sixth cervical vertebral body. Other findings include soft tissue air-fluid levels, and cervical retro flexion.

Lateral neck radiograph demonstrating widening of the retropharyngeal space and reversal of the normal cervical spine curvature. The retropharyngeal space normally measures one-half the width of the adjacent vertebral body and is considered widened if it is greater than a full vertebral body at C2 or 3 when the spine is properly extended in an infant or child younger than 5 years of age. The epiglottis and subglottic area in this radiograph are normal.

- Croup – Anteroposterior and lateral neck radiographs are sometimes used in evaluating children with suspected laryngotracheitis (croup). Typical radiographic features include the “steeple” sign, which occurs when the subglottic arch becomes edematous and shows an inverted “V” in the anteroposterior view. In the lateral view, the hypopharynx is distended and there is subglottic haziness. The epiglottis is normal. Unfortunately, these signs are not consistently present, so the plain radiograph has limited value in distinguishing between croup and epiglottitis.

The anteroposterior (AP) view demonstrates tapering of the upper trachea, known as the “steeple sign” of croup. Note that the finding can be simulated by differing phases of respiration even in normal children.

Lateral neck radiograph showing subglottic narrowing (arrow) and distended hypopharynx (arrowheads) consistent with acute laryngotracheitis.

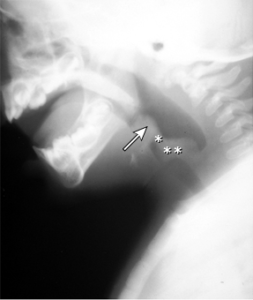

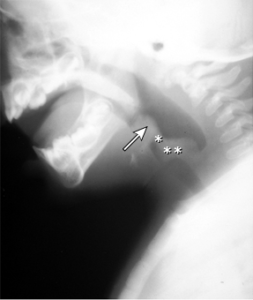

- Epiglottitis – If lateral neck radiographs show an edematous epiglottis with the thumb sign, enlarged aryepiglottic folds, and a ballooned hypopharyngeal airway, epiglottitis should be considered. However, these findings are subjective, and as many as 70 percent of all patients with epiglottitis have radiographic findings interpreted as normal.

Lateral neck radiograph demonstrating swollen epiglottis (arrow) and aryepiglottic folds (asterisks) in a child with epiglottitis due to Haemophilus influenzae type b. The swollen epiglottis is often called a “thumb sign.”

Chest radiographs — In cases where an intrathoracic problem is suspected, a plain chest radiograph should be obtained. Plain radiographs can demonstrate mediastinal lymphadenopathy or masses. Findings suggestive of vascular rings, including a right aortic arch, may also be identified on plain films. Findings suggestive of foreign body aspiration include mediastinal shift, unilateral hyperinflation, atelectasis, or the actual foreign body, if it is radiopaque. However, a normal chest radiograph cannot completely rule out an airway foreign body because most of the objects aspirated by children are radiolucent

Other studies — Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and neck with contrast can be helpful in the diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess. It is also used to look for enlarged lymph nodes, tumors, aberrant arteries, and vascular rings, but intraluminal lesions are easy to miss. In addition, it may show narrowing of the airway suggestive of tracheal stenosis, but does not provide optimal imaging of the trachea along its long axis. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the airway from CT scans may also better define an obstructive process and can be done on request.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is valuable for evaluation of children with suspected tracheal stenosis or obstruction because it is able to image the trachea across the long axis. When performed without contrast injection, MRI can also provide an estimate of the length and degree of a tracheal stenosis or obstruction, if present. It also provides a good evaluation of the mediastinum. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is usually used to define vascular anatomy in children if a vascular ring is suspected after plain radiography.

Barium swallow is a useful test to identify swallowing dysfunction, or esophageal abnormalities.

When laryngomalacia is suspected, a laryngoscopy is a quick way to confirm this diagnosis. It can be done in the office or bedside and does not require sedation.

For children with suspected tracheomalacia, airway fluoroscopy may be helpful since it shows the airway dynamics during breathing, but the definitive diagnosis usually is made by bronchoscopy.

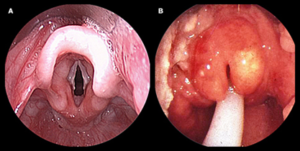

Airway examination — Visualization of the airways with nasopharyngoscopy, laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy allows definitive diagnosis of the cause of stridor in children. More than one airway abnormality may be present in the same child, and a thorough evaluation of the upper and lower airways may be warranted.

Airway visualization with the intention of intubation should be promptly performed if the underlying cause of stridor in an acutely ill child is thought to be epiglottitis or bacterial tracheitis. Patients with suspected or known foreign body aspiration also require examination of the airway, usually as part of a procedure to remove the foreign body.

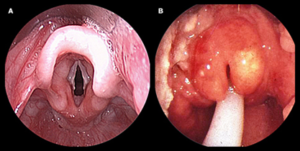

(A) Normal epiglottis.

(B) Characteristic erythematous, edematous epiglottis of acute epiglottitis.

Note the adherent mucopurulent membranes within the trachea.

- Nasopharyngoscopy is appropriate for the patient with a stable airway and can be performed in an unsedated and awake child at the bedside. Nasopharyngoscopy is useful in the diagnosis of laryngomalacia and anatomic defects between the nose and pharynx, as well as in the assessment of vocal cord movement.

- Flexible or rigid laryngoscopy and/or bronchoscopy are appropriate for the patient with an unstable airway, or for those with suspected foreign body aspiration. These procedures should be performed in the operating room, with anesthesia, sedation, and continuous monitoring. In cases of suspected epiglottitis, direct laryngoscopy usually can be performed safely by experienced interventionists with little risk of complications such as laryngospasm

Airway visualization is also indicated for many patients with chronic or intermittent stridor, to evaluate the airway and establish a diagnosis. Rigid laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy are the gold standards for evaluation and diagnosis of subglottic, tracheal, and central airway lesions. The rigid bronchoscope allows the clinician to take biopsy samples, remove foreign bodies, and dilate stenosed airways, if necessary. If a foreign body is not suspected, a flexible bronchoscope is usually used, and the examination is performed during spontaneous breathing to help identify abnormalities in airway dynamics, including laryngomalacia.